Esko Rahikainen, University of Helsinki

Translated by Nicholas Mayow

Aleksis Kivi was born into a tailor’s family in the province of Uusimaa in Finland, at a village named Palojoki which is in the parish of Nurmijärvi, on October 10th, 1834.

His parents were Eerik Stenvall and Anna-Kristiina Hamberg and they already had three sons. After Aleksis, they had a daughter named Agnes, who died when she was thirteen. Kivi’s great-grandfather had had a soldier’s croft in Palojoki since 1766 but, from time to time, the family had also lived in Helsinki. According to Yrjö Blomstedt, his earliest-known ancestors came from Janakkala. His maternal grandfather, Antti Hamberg, was a blacksmith at a place called Nahkela in Tuusula, his paternal grandfather, Antti Juhana Stenvall was a seaman who had sailed as far as the Mediterranean. Uncle Kalle Kustaa was in the Finnish Guards and helped to put down the Polish uprising. The writer’s own father, Eerik Stenvall, had lived in Helsinki as a child and gone to school there.

Aleksis’ parents could speak Swedish, a skill which the boy acquired himself by moving to Helsinki to go to school; it was a necessity for matriculation and for further study for the priesthood. In fact, Kivi seems to have spoken Swedish distinctly more than Finnish during his lifetime. Between the years 1821 and 1868, only seven boys from Nurmijärvi passed the matriculation examination to become university students. Of these, Aleksis Stenvall was the only commoner, the others were all children of persons of rank. In the year he matriculated, 1857, Kivi made a critical and historic decision from his own point of view and from the point of view of literature, to become a writer in the Finnish language instead of a priest.

Aleksis Kivi, which he used for the first time as a nom de plume in conjunction with the manuscript of Kullervo, in 1860, was unable to travel abroad for financial reasons, yet he did visit Turku. However, his reading and along with it his horizons, extended far beyond school and university textbooks, to the literature of the whole world.

Only a fraction is known to researchers, but Kivi read everything he could lay his hands on, from Held and Corvin’s History of the World to works dealing with chemical analysis, newspapers, the poems of Stagnelius and the plays of Shakespeare, which are known to have been an influence on him.

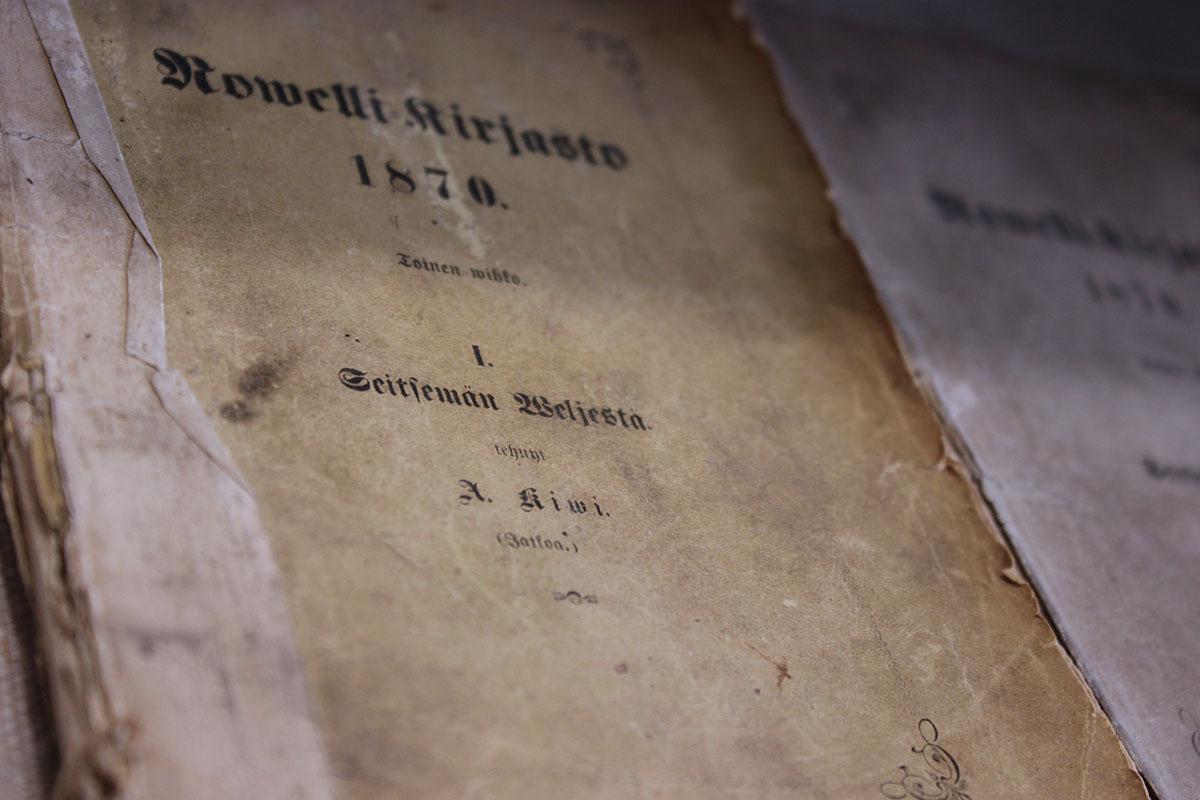

Kivi’s most important literary works could be considered as beginning in the mid 1850s, with the play Nummisuutarit (The Wedding Dance) and ending with the play Margareta, which was published in 1871. The play Nummisuutarit, which came into being as the result of the development of the Finnish language, was awarded the State prize for literature in 1865 and is still today the most frequently performed play ever written in Finnish.

Kivi’s most important supporter was Fredrik Cygnaeus, professor of aesthetics and modern literature, who examined Kivi for the matriculation examination and who, from the time of Kivi’s very first prize, right up to Kullervo, Nummisuutarit and Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers), which has attained the status of a national novel, repeatedly placed his whole expertise and authority behind Kivi’s talent and art. Of his opponents, those narrow-minded captives of literary tradition, the most famous was August Ahlqvist, professor of Finnish language and literature, who achieved an undying reputation by belittling Kivi’s works.

Karl Bergbom, the theatre director who made Kivi’s plays familiar to the general public, starting with a performance of Lea in 1869, became Kivi’s friend and researcher as early as 1864. In his books, the writer named his school and university friend Robert Svanström, who later became a forestry official, as his best friend.

It seems probable that in the development of many of his important poems, and of Kihlaus, Nummmisuutarit, Lea and Seitsemän Veljestä it was in fact an advantage that Kivi had to write them in a completely Swedish-language environment, at Fanjunkars in Siuntio, where he was forced into isolation from his friends through lack of funds. He took this very heavily at times and in his letters he expressed his longing for the company of his friends and his homesickness for the parish of Nurmijärvi.

Besides Cygnaeus, Charlotta Lönnqvist the mistress of Fanjunkars could, without exaggeration, be described as the writer’s most important supporter.

From a large group of admirers it is worth mentioning Kivi’s beloved Albina Palmqvist, daughter of a Helsinki clothing manufacturer and Aurora Hemmilä, a Mäntsälä inn-keeper’s daughter. Marriage was impossible, however, since in the society of the civil servant class, Kivi lacked the most essential things of all, an official position and the income that went with it. In his works, Kivi also wrote about his yearning for a family of his own. Socially, Aleksis Kivi fell between two stools in a rather ill-fated way; he was no longer a vulgar peasant but neither did he belong to the gentry.

The fount of strength in Kivi’s career as a writer was his incredible imagination, his knowledge of people and his literary talent and, at the same time, the love and sympathy towards ordinary people that appears over and over again in his works – incomparable humour as well as a sense of tragedy and comedy.

Aleksis Kivi was a product of three localities – Nurmijärvi, Helsinki and Siuntio – and all of them had their own essential importance to his growth as a person and as a writer. Kivi’s mother’s home parish of Tuusula provided a final resting place for the author, who suffered in the last years of his life from mental illness. At the time of his death on the night before the last day of 1872, Aleksis Kivi was only 38 years old, but as a writer he is ageless. Seitsemän veljestä and Nummisuutarit are classics of Finnish culture on a par with the Kalevala and the Kanteletar.

The Cornerstone of Finnish Literature

Anto Leikola, Professor Emeritus of History of Science

Alexis Stenvall, generally known by his pen name Aleksis Kivi, has been called the cornerstone of Finnish literature. The epithet fits him well, because ”Kivi” actually means ”stone”. He was born the 10th of October, 1834, as the youngest son of a poor village tailor in the parish of Nurmijärvi, some 30 km north from Helsinki, and he died the last day of December, 1872, in his brother’s cottage in the neighbouring parish of Tuusula, only 38 years old. By then he had written and published the novel ”Seven Brothers”, several comedies and tragedies, including ”The Cobblers on the Heath” and ”The Engagement”, and a quantity of beautiful poems. The novel is still considered as one of the foremost in our literature, his plays are performed nearly continuously in different theatres – most of them have been filmed, too – and many of his poems have reached an everlasting life as songs composed by the foremost Finnish composers, including Jean Sibelius.

Kivi was born in a time when Finland, formerly a group of provinces in the Swedish Kingdom, had a quarter of a century earlier become an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, with the Russian Czar as the Grand Duke. The language of nearly all higher culture was still Swedish, and practically all of the existing literature in Finnish language consisted of the Bible, some religious books, the hymn book and the Law of the Swedish Kingdom. There was one university, which in 1828 had been moved from Turku to Helsinki, and all its education was given in Latin and Swedish; also all secondary schools were Swedish.

Kivi’s father had got some education, so that he could read and write in both Swedish and his native Finnish, and the young Alexis learned reading and writing under the village schoolmaster. He was anxious to learn more, and so he was sent to a proper school in Helsinki, where he learned Swedish and could proceed in his studies to the secondary school level. After many years and several breaks in schooling – some of them because of sheer poverty – he could pass the University entrance exam. He seems to have had no special plans for further studies, because he had abandoned the idea to become a Lutheran clergyman, an idea cherished by his mother, and he never mentioned anything about a possible career in the civil service. He listened in the University the lectures of at least Professor Elias Lönnrot on Finnish folk poetry and Professor Fredrik Cygnaeus on world literature and poetry. It is known that he read much foreign literature in Swedish translations; especially close to him were Shakespeare and Cervantes. But what is most important, he had began his own writing.

Lönnrot and Cygnaeus belonged to the generation which was born in the earliest years of the nineteenth century. Lönnrot had worked many years as a country physician in Northeastern Finland and collected a great mass of Finnish and Karelian folk poetry, of which he composed the famous national epic ”Kalevala”, published in 1835, a year after Kivi’s birth. Another member of the same generation was the poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg, who published a quantity of lyrical poetry – in Swedish – and two collections of patriotic poetry, praising the bravery of the Finnish soldiers fighting in the Swedish troops in the 1808-1809 Swedish-Russian war. One of Kivi’s dreams was, as he told his mother, to become a poet like Runeberg. A very important figure, both for Kivi and for the whole nation, was the philosopher and politician Johan Vilhelm Snellman, who laid the foundations of thinking of the Finnish people as a separate nation. He and Cygnaeus had, so the story goes, by accident seen the Swedish manuscript of a comedy by Kivi, and Snellman, whose own mother tongue was Swedish, exhorted the young man to write in Finnish.

In 1859 Kivi had finished his play ”Kullervo”, based on the ”Kalevala”, and won the first prize in a contest organized by the Society for Finnish Literature, founded in 1831. Thus his name became known in the Helsinki literary circles, not only among the young Finnish-minded students, of which many became his personal friends. His next master-piece was the comedy ”Nummisuutarit”, or ”Cobblers on the Heath”, which he published on his own expence in 1864. The following summer he received a State Award in a contest where Fredrik Cygnaeus was the chairman of the board. Several eminent writers, including Runeberg himself and August Ahlqvist, the Professor of Finnish language and also a Finnish-language poet, were defeated. During the early 1860s Kivi had dwelled in different places, sometimes at Helsinki and sometimes in the countryside, but in 1864 he settled in Siuntio, some 50 km west from Helsinki, in the house of Charlotta Lönnqvist, a Swedish-speaking lady nearly twenty years older than Kivi. The relationship of Alexis and Charlotta has never been fully clarified, as many writers believe that she was his mistress and many others deny such a possibility. He anyway lived seven years with Charlotta and had there excellent opportunities to write new plays – altogether about a dozen – and concentrate in his great novel, ”The Seven Brothers”. The novel was finally published by the Society for Finnish Literature as a part-work, but the influential Professor Ahlqvist wrote about it a murdering criticism, and the Society did not dare to sell it any more, nor to bind it as a whole book. In 1871 Kivi’s health deteriorated, and the first symptoms of a mental illness became evident. He was brought to the mental hospital of Helsinki, and after nine months there his brother Albert picked him as ”an incurable case” to his home at Tuusula, where Kivi died in the end of the year 1872. His last words were reportedly ”I am alive” (or ”I shall live”). His friends organized quickly a funeral, and before the coffin was closed, one of them drew a picture of his face, the only portrait that exists of this hero of the Finnish literature.

The sceneries of Kivi’s plays are varied. ”Kullervo”, named after a rebellious hero in the ”Kalevala”, deals with the mythological past, ”The Refugees” happens in the environment of a South Finnish mansion, ”Canzio” brings us to Italy (which Kivi never visited), ”Beer-trip to Schleusingen” was inspired by an episode in a small German town during the Bavarian-Prussian war in 1866, and ”Lea” is located in Biblical Israel. But the best and most beloved of Kivi’s plays describe common people at his native Nurmijärvi. The one-act ”Engagement” tells the story of a middle-aged tailor who considers a possible engagement with a bad-tempered woman, living as a so-called housekeeper with a couple of gentlemen. She has consented to the engagement only because of one of her caprices and a sudden anger towards her masters. The protagonist in ”Heath Cobblers” is Esko, a cobbler’s son, whose father, because of a misunderstanding in a pub, believes that the son has been engaged to the farmer Karri’s daughter. Esko prepares himself for the wedding and goes to the farmer’s house, together with his unreliable companion Mikko. When they arrive to Karri’s place, they find that a wedding is already going on, as Karri’s daughter has been wed to a young carpenter. After many adventures Esko and Mikko believe that they have caught a dangerous robber and, together with Esko’s brother and uncle, they bring their prey home, only to find out that the supposed robber is an honest sailor, father of the cobbler’s stepdaughter. The play ends with Esko’s comment that he will never again think about marriage. The focus of the comedy is not so much in the story itself but in the protagonists’ characters, especially the simple and honest but stubborn Esko, and many of his repliques have become nearly proverbial in Finland.

”The Seven Brothers”, Kivi’s only novel, describes seven young men, orphaned relatively early, who try to manage their farm Jukola but get into conflict with the neighbouring village society. A particularly hard trial is their inability to read, which would be necessary for a full membership of the Lutheran Church, including the licence to get married. The brothers decide to move into a remote forest region – still belonging to their farm – and build a new house there. A fire in full winter forces them to return, but next spring they move back and stay as forest-dwellers for ten years. Meanwhile, they have finally learned to read and know the Catechism, and then they can return to their old Jukola as mature men and full citizens, reconciled with the society. Later on, they all, except one, marry and establish their families in their own farms, separated from the vast lands of the native Jukola. Thus the novel tells about human development and maturing, but still more it describes the South Finnish countryside milieu with village and forest life, and the protagonists’ individual characters which many Finns feel are ”flesh from their flesh and blood from their blood”.

Even here, many of the brothers’ sayings have become proverbial among practically all Finns.